“It had not only a local impact but a global impact as well”

What Steven asked Richard Morsley, Chief Executive of Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust

Richard Morsley is the Chief Executive of Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust. Steven met Richard in his office as dockyard ends its 2024 season. This was more challenging than expected and required the help of the friendly Dockyard team after Steven got lost in the vast space within the Dockyard walls. They discussed what brought Richard to Chatham Dockyard, Tom Cruise flying in via helicopter, the future of rope making, and whether a ship in Portsmouth should return to Chatham.

We're in the Fitted Rigging House?

Amazing building, a huge brick-built warehouse for the Royal Navy. It's Grade I listed, scheduled ancient monument. It was sitting for years as a largely underused, underutilised space. The challenge for the Trust was how do you turn a heritage liability into a real asset. I think that's what we've been really successful in doing over the last 40 years. We put together a project, we secured funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund, from DCMS, Department of Culture, Media and Sports, as well as a number of other funders and a major individual donor.

What timescale was this?

This was 2016, 2017. Relatively recent, and the project involved a whole raft of public benefit uses on the ground floor. We updated and refreshed our steam, steel and submarines gallery, which is effectively the Dockyard’s 19th and 20th century story. We created a fantastic new reading room from our archive, as a resource for both volunteers and any others who wanted to come and research here. We created new conservation facilities, we created a new archive storage for the Trust's archive and our collection.

Alongside that, we built 50,000 square feet of commercial space, which enabled our longer-term financial sustainability. This organisation has very much had an eye on that underlying financial model. How do we, as an independent museum and independent charitable organisation, ensure our ongoing viability? That project completed in late 2018, early 2019. It was fully let from the day it opened and remains let to this day and here we've got a whole raft of businesses, anything from Dovetail Games, MKC Training and a range of other businesses located out of the dockyard. What was brilliant was that that project effectively developed about two-thirds of the building, leaving one-third of the building at the southern end undeveloped. We'd done the roof, we'd done the windows, and the building was fully watertight and weatherproof.

Was that intentional to leave the southern end?

Budgets necessitated we worked in that way. Then we secured some additional funding through the Levelling Up Fund. There was a Chatham package of works in the first round, which involved the Dockyard and the Docking Station, which is going to develop at the northern end of the estate.

We took that remaining one-third undeveloped of the site, about another 20,000 square foot of space, and we took that money and we developed it for commercial use. Once again, that building is fully occupied. This building today generates long-term sustainable revenue through property lettings which enables us to fulfil our charitable purpose of both preservation and learning. It's been a really remarkable project.

Families come to visit a submarine and grab a pie, unaware of the community developing around them.

It's an amazing place. It's a living, breathing community. We have just shy of 200 businesses based out of the Dockyard that employ probably in the region of about 800 people in total. We're an educational campus for the University of Kent and MidKent College. We're a residential estate for nearly 400 people. We're a museum and visitor attraction that welcomes probably 170,000 visitors this year. We're an event space, we're a film location, we're a ropemaker and much more. It just creates this thriving, interesting, mixed-use estate that we are today. We're hard to characterise in a business estate. As a charity, we're essentially a preservation and learning charity. If you distil it right back to who we are, what we do, why we are here as an organisation, the Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust, our charity, is the custodian of this remarkable 80-acre historic estate. In our care we have 100 plus buildings and structures, 53 Grade I and Grade II listed and 48 scheduled ancient monuments.

What is the difference between Grade I, Grade II, and ancient monuments?

It just denotes their significance really. Listed buildings are dealt with through the local authorities. Scheduled monuments are the highest categorisation, the highest protection really afforded to historic buildings. That's administered through Historic England.

Who owns the buildings?

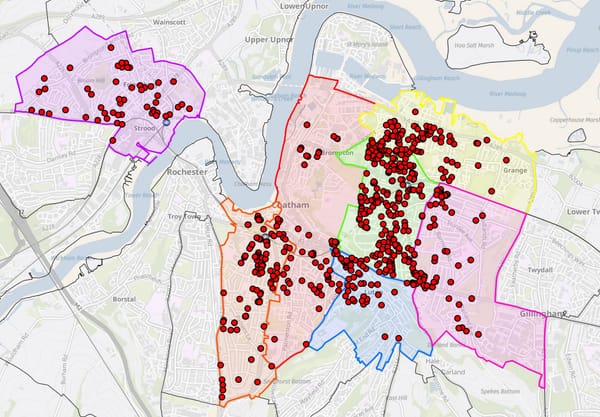

The Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust. We effectively have a virtual red line that runs around the estate. It follows the river along, out to the southern extent, up to Medway Council, effectively up to the dockyard wall. It follows around the dock wall all the way down to Dock Road, down towards Chatham Maritime. Then it loops around the ponds. The boundary gets a bit messy at the northern end of the site and then effectively comes back in behind what we call our covered slips and then comes back along the river, so that's about 80 acres in total.

It can be hard to get your head around how big the historic dockyard was. What dictated what became the Trust and what didn't?

You're right to say that the former working dockyard site and estate was much larger than today's Chatham Historic Dockyard. Previously, the dockyard would have been probably 350 to 400 acres, would have gone northwards out through St Mary's Island, the three basins that we have at St Mary's Island, out to what's today's Chatham Docks, coming back through to what's today's Pembroke, the universities, and through what's today's historic dockyard site. At the point of closure of the dockyard in 1984, the land was parcelled up into three large parcels of land. This core historic estate was kept together as a site of strategic historic significance, which the ownership of which was transferred to the Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust. The land to the north of us out towards what's today St Mary's Island. That went to English Estates, the government's then regeneration agency and has been successfully redeveloped over those 40 years to be the Chatham Maritime through the Chatham Maritime Trust, a thriving residential and commercial estate. The Universities at Medway sits within that estate as well. The final piece of land in that is what's today's Chatham Docks.

Why was Chatham so important that they put such a large dockyard here?

For 400 years, this place was the home of the Royal Navy on the River Medway. Chatham's significance first established in the Stuart period. The first known establishment on this site dates to about 1618. You can't see any of the Stuart dockyard on the estate today, it's all in archaeology. The oldest part of our site is actually in archaeology underground, protected and scheduled because of its significance. The significance of this place for the Royal Navy, which grew through that Stuart period, was much to do with the geopolitical situation in the world at that time. Much of the conflict we're really looking towards the near continent, the Dutch, the French, the Napoleonic Wars. The Medway was ideally situated to get out into the North Sea and the English Channel. Chatham's role subsequently changed over time as a greater focus was on the Americas. Then subsequently, Portsmouth and Devonport were actually much better positioned to get the Royal Naval ships quickly out onto the Atlantic.

Through the 18th century, that political world order changed, and it became very much the leading shipbuilding and repair yard for the Royal Navy. The dockyard that you see here today is very much that dockyard of the age of sail. This real age of significance through the late 17th and 18th century is really this place's moment of huge, huge significance and early into the 19th century. It was one of the largest industrial complexes anywhere in the world. It was hugely, hugely significant. It had not only a local impact but a global impact as well. Then in the Victorian period, ships were getting ever larger and larger. They were finding they couldn't actually get round to the River Medway in terms of its current location and the dockyard extended northwards. Into what's now St Mary's Island. The creation of the three large basins that are now on that site was really about how to cope with ships that were becoming ever larger. Which is also why this place remains so complete today because instead of having to knock down and build on top of the buildings that were here, they were just able to extend northwards.

You mentioned submarines as well?

Chatham's role changed to submarine construction, as well as refitting and repair for other ships, right the way through to the last submarine being built for the Royal Navy in Chatham, HMS Ocelot, which is in the Trust's care. HMS Ocelot was built in May 1962 and launched into the river. Then there were subsequently, I believe, three further submarines built for the Canadian Royal Navy in Chatham, at which point that long tradition of shipbuilding in Chatham came to an end.

When I was walking down here, I discovered beehives, which I wasn't expecting. How big is the team running the estate?

It is the weird, wild, and kind of wonderful world of the historic dockyards. I should have said, our overarching strategy here, nearly 25 years on, is one of preservation through reuse. We believe that it's the reuse of this place that keeps it living, breathing, thriving, and relevant. Myself and our team, we're part of that community. There's never a dull day in the dockyard, I think that's fair to say. We're probably in the region of about 120 to 130 people in total. A sizable team. That's made up from our front-of-house teams, our catering teams, and our learning teams as part of that. We're an independent museum. We receive no public funding. This organisation doesn't receive any public funding for its core charitable purpose and core activity. Everything that we do is 100% self-generated on a revenue basis. All of our day-to-day operations as a charity, we're probably in the region of about eight and a half million-pound turnover annually. All of that is self-generated, and that's through our commercial estate, through our museum, through our commercial activities that underpin that as well.

With the buildings, it can be hard to work out what is used for what. There is a large church on site. Is it a working church?

It is a scheduled monument. It's not a working church. It's fit out effectively as a conferencing venue. It was previously a lecture theatre for the University of Kent's Business School, which they vacated last year and moved across to Pembroke.

Commissioner's House?

A wonderful, wonderful building.

It's not a test. I'm not going to go through building by building.

I'm glad you asked about it actually. Grade I listed scheduled ancient monument. It is the oldest intact naval residence in the world. It is actually our next major project, which we're delivering on our site. We've just secured £2.3m of capital funding from Arts Council England for a big preservation project for the building. It's going to undergo the best part of an 18-month preservation job and major refurbishment. It's going to get a new roof, a mechanical and electrical refit inside, and new windows, which will all be refurbished, but with a really honest job back to those early Georgian traditions and style. All overseen and working really closely with Historic England as a scheduled monument and ultimately will be used as a hospitality venue. I think, once again, it demonstrates some of the challenges of being responsible for this incredible but large diverse, incredibly expensive historic estate to maintain. I mean, it's the best part of a three-million-pound project on one building alone. You amplify that across our hundred buildings and structures across our estate. It's an expensive place to manage and maintain. On the one hand, we talk about being financially independent and achieving this position of financial self-sustainability on a revenue basis. Those big capital projects and securing that external funding to enable the preservation of this place is absolutely vital, and over the 40 years of the Trust, we've generated nearly £70m of capital to enable us to manage and maintain this place.

Another part of the mix you mentioned is housing. How much housing is there on the site?

Along the eastern flank of the dockyard estate, running quite closely to the dockyard wall as it goes down Dock Road. There's a residential estate there that was built out in phases over the 90s. I believe it's 115 residential properties, and they're a mixture of new builds, which were sympathetically built and designed, which are quite private and discreet within the wider dockyard estate. Then there's also the reuse of a number of historic buildings, including our beautiful Officer's Terrace, which are all in single private ownership, of townhouses that were once both the offices and the homes of the officers of the dockyard.

Housing is a wider issue for Medway. Is there any further capacity on the site for more housing?

I would say probably no capacity on the core historic dockyard site. I did mention previously these two sites that are right on our northern boundary, which sits outside of the Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust control, but which are owned by Homes England. There is a proposal on those two sites for a residential scheme.